THE COST OF POLICING – Evaluating Kamloops’ law enforcement future

RCMP officer guards crime scene in Kamloops.

By PETER TSIGARIS

Thompson Rivers University

Prelude: This is the third editorial of the book series I co-authored with my senior undergraduate students, titled: In the Shadow of the Hills: Socioeconomic Struggles in Kamloops, published by TRU Open Press.

Patrick Izett.

This editorial is the work of Patrick Izett who examines the economic and social implications of different policing models. By considering costs, crime rates, community engagement, and governance, Patrick assesses which policing model best serves Kamloops’ long-term interests.

The research is featured in Chapter 4: Transitioning to Local Authority: Practical Steps & Challenges. Below, I summarize his research and key findings.

Law enforcement structure

Kamloops currently relies on the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for policing services, but transitioning to a municipal police force or a hybrid type model could provide a better service. Patrick explores Kamloops RCMP services and compares it to the municipal police in Saanich, Delta and Westminster.

The Economic Burden of Policing Choices

The cost of policing includes both direct and indirect costs. Direct expenditures cover operational expenses, while indirect costs encompass factors such as crime prevention effectiveness, response efficiency, public trust and the broader societal impacts of crime, including lost lives and economic losses due to victimization.

Kamloops currently allocates approximately 18% (i.e., $33 million in 2023) of its operating budget to policing, lower than Saanich (30%) and Delta (21%), but higher than New Westminster (16%). While, RCMP services are partially subsidized by the federal government, the question is whether transition to another system would yield additional benefits that justify the extra costs.

Comparing similar-sized cities reveals an important trend: municipalities with independent police forces tend to have lower crime severity indices (CSI). Kamloops’ CSI of 156.7 is significantly higher than New Westminster (84.7), Delta (60), and Saanich (51.3).

While this correlation does not necessarily indicate causation, it is possible that cities with lower crime rates are more likely to opt for municipal policing, or that municipal policing itself contributes to lower crime rates.

The relationship could also be bidirectional, where both factors influence each other. Nonetheless, the data suggests that municipal police forces may offer some additional advantages in terms of crime reduction and community safety.

Public Safety and Policing Effectiveness

Given the high crime rate in our community and a high officer-to-population ratio of 689 residents per sworn officer, this suggests a need for additional officers to meet community safety demands. Municipal forces, governed by civilian-led police boards, may have more flexibility to adapt staffing levels and crime prevention strategies to local needs or a hybrid type of model.

Patrick conducted interviews with an RCMP and a municipal officer, where key challenges emerged. The RCMP officer cited staffing shortages, recruitment difficulties, and limited local control as barriers to effective policing in Kamloops.

On the other hand, the municipal officer, while also facing recruitment challenges, highlighted the advantages of localized decision-making, stronger community ties, and a relatively efficient usage of scarce resources. Both emphasized proactive policing strategies, such as increasing visibility in high-crime areas during peak hours.

Potential Pathways for Kamloops

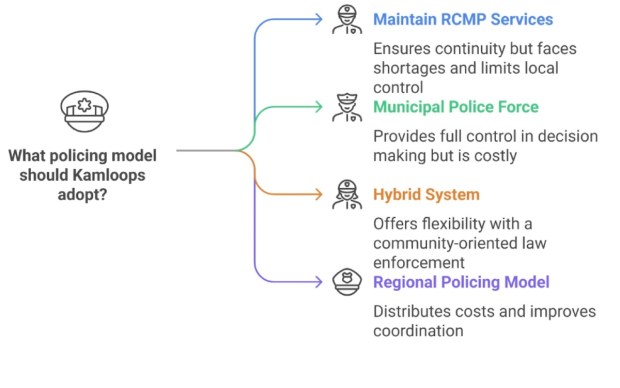

Kamloops has four primary options according to Patrick:

- Maintain RCMP services under the current contract. This option ensures continuity in policing but may limit local control and responsiveness to Kamloops’ specific needs.

- Transition to a fully municipal police force. While costly, this approach provides full control over policing strategy, recruitment, and community engagement.

- Transitioning to a hybrid RCMP-municipal police system would involve integrating elements of both federal RCMP services and local municipal policing to create a flexible, community-oriented law enforcement structure. This system could be designed to gradually transition Kamloops toward greater local control while still leveraging RCMP resources

- Consider a regional policing model. Forming a Thompson-Nicola Police Service could distribute costs among neighboring municipalities, improve interagency coordination, and enhance policing efficiency. This model was explored in research as a potential pathway but comes with challenges such as initial setup costs and governance complexities.

Figure 1: Alternative police systems, Image created by Napkin AI

An addition to any policing system is to:

Integrate AI and robotic technology into policing. Implementing AI-driven predictive analytics, robotic surveillance, and automated response systems could modernize law enforcement, improve crime prevention, and reduce officer workloads. However, ethical considerations, privacy concerns, and funding requirements would need to be carefully managed.

Conclusion

Policing decisions should not be made lightly. The choice between maintaining RCMP services, transitioning to a municipal force, exploring a hybrid model, and a regional policing model with the integration AI and robotics involves financial, social, and governance considerations. The data suggests that municipal forces are associated with lower crime rates and stronger community ties, but they come at a higher cost. If Kamloops moves toward a new policing model, careful planning will be essential to ensure a smooth transition and sustained public safety.

I invite readers to share their thoughts on this critical issue. What do you believe is the best path forward for policing in Kamloops?

References available in Chapter 4: Transitioning to Local Authority: Practical Steps & Challenges

Tsigaris, P., Awad, A., Forbes, C., Izett, P., Kadaleevanam, U., Mehta, G., Noor, S., Simms, O., & Thomson A. (2024), In the Shadow of the Hills: Socioeconomic Struggles in Kamloops, TRU Open Press, https://shadowofthehills.pressbooks.tru.ca/

Good day all. Having policed New Westminster in the mid-80’s to early 2000’s, our use of both community policing initiatives and downtown foot patrols paid favorable dividends. I was told–early in my career–that some the RCMP in northern communities were sometimes referred to being “police officers without legs.” The inference being made here is that the police drove around in their police cars but were rarely seen getting out of them and actually walking. This suggested that, with the exception of pure enforcement activities where face-to-face contact was/is a must, that the police were seen to be otherwise aloof, uncaring, and otherwise not fully engaged in the community.

In the early to mid 1980’s, some of referred to New Westminster as “The Wild-wild Westminster,” as Friday and Saturday nights brought some 5,000 bar patrons into New Westminster (this was roughly the total number of bar seats in a city of less than 60,000) with the result being numerous and ongoing incidents of public drunkenness, bar fights, and impaired driving. Add to this, a total of five SkyTrain stations that brought their fair share drug dealers, thieves, and other ne’er-do-wells, and the street crime in the city was staggering.

Four things made a significant impact in policing the City of New Westminster:

So, may I suggest, that regardless of the model that one chooses, these “keys to success” must be present to create and maintain effective policing. A multi-pronged approach is necessary that includes enhanced face-to-face interaction between: citizens and the police; offenders/potential offenders; business leaders/proprietors; community groups; the Crown Counsel’s office; the Mayor and City Council; and other affected stakeholders in the community in order to make policing truly effective.

With 28-years of policing/law enforcement experience—retiring as a manager with the Vancouver Police Department—I hope that this helps!

LikeLike

The student concluded “It is found that there is a correlation between having a lower socioeconomic status and crime rates.” but they didn’t report ANY statistics, any p-values, anything that would speak to either the strength of that correlation or the veracity of it.

LikeLike

Thank you all for your comments. Patrick and I appreciate all constructive feedback and will be considered in the research as we move forward.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. I’d like to clarify that the conclusion you’re referring to – the correlation between socioeconomic status and crime rates – is not my student’s original finding, but rather a summary of the literature, specifically drawn from Kitchen (2007), a study commissioned by the Department of Justice Canada.

Patrick’s research focused on the potential transition of Kamloops’ policing system from RCMP to municipal or hybrid models, and the practical, economic, and governance implications of that transition. The reference to socioeconomic factors and crime was used to contextualize broader issues that affect policing outcomes, consistent with the literature review. The student appropriately cited this in both the literature and conclusion sections, without claiming original statistical analysis on this point.

It’s important to distinguish between a literature-based observation and an empirical conclusion derived from original statistical testing. The student did not misrepresent the claim, nor was the purpose of the research to quantify that specific relationship. Rather, the study aimed to explore how policing structures might better address the challenges faced by communities like ours.

I appreciate your engagement, but I also encourage a more careful reading of the student’s objective and scope. The critique about missing statistics would be more relevant if the claim were being presented as a new empirical result, which in this case, it was not.

References:

Kitchen, P. (2007). Exploring the link between crime and socio-economic status in Ottawa and Saskatoon: A small-area geographical analysis. Department of Justice Canada, Research an Statistics Division. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/crime/rr06_6/rr06_6.pdf

LikeLike

A major weakness for the argument toward municipal forces, is that the very people who got this town into this mess would be responsible for setting the force’s agenda.

Imagine a bunch of progressive pro-drug binge safe supply crackerjack councillors in charge of keeping the community safe?

We can’t even get them to do basic things like clear encampments. Instead, they want the citizens and their kids to go pick up needles and encampment trash on the beaches.

Family fun for everyone!

LikeLike

No, the public is not being asked to pick up needles on the beach. The City does a pre-cleanup of anything dangerous prior to public cleanup day.

LikeLike

A hybrid model consisting of provincial and municipal policing such as Ontario and Quebec have (Alberta is currently considering) would be an interesting avenue of study considering these 2 provinces have by far the lowest crime rates in the country. I’ve also wondered, would a regional force incorporating the Okanagan (largely administrative and planning) be of practical use?

On a sad note, 5 of the top 10 crime severity indexed census metropolitan areas (CMA= 100,000plus pop) in the country are from BC (we only have 7 cma’s), neither Vancouver or Victoria were among them nor were any from Ont. or Que., so this is clearly not a big city driven problem.

LikeLike

That Saanich, Westminster and Delta are a relatively calmer and safer places because they have a municipal police force is hard to agree with. Maybe a more comprehensive comparison needs to be done to give us greater insight.

But since a big chunk of police costs are spent in chasing a relatively small group of people doing the same (bad) things over and over I wonder if the research could focus on a new definition of insanity. It is clear the demand for Cocaina is there and the police (RCMP, FBI, or local police) despite the billions spent can’t do a thing about it.

LikeLike

Saanich and particularly Delta are suburban cities so they absolutely wouldn’t have the same inner city issues that we have and New Westminster have transit police along with being a relatively tiny geographical area to cover which combined may screw the numbers. I would think Lethbridge would be a fair comparison as they have municipal policing.

LikeLike

Considering the huge negative “baggage” the national police force carries it is probably a good thing to switch. However a complete independent police board needs to be set-up for this to work. We cannot let hidden interests, egos and jealousy to make it another pointless advisory scheme…we have too many of those already.

LikeLike