A look at the market forces behind the rise, fall and long-run equilibrium of copper prices

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Peter Tsigaris is a professor of Economics at Thompson Rivers University. He writes for The Armchair Mayor News about issues of importance.

By DR. PETER TSIGARIS

There has been a lot of talk lately about the falling price of copper and speculation as to where that price is heading in the future.

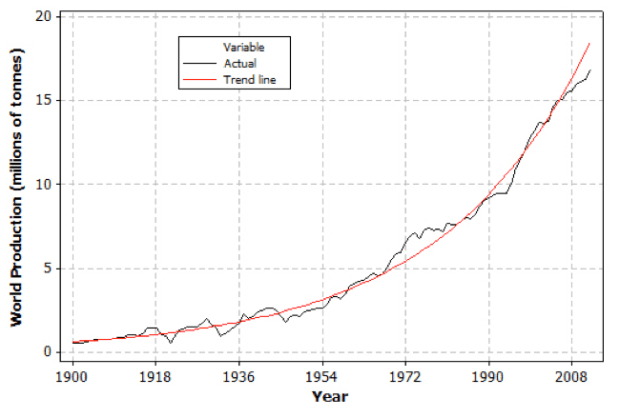

But let’s start with the world production of copper. World production has been increasing exponentially at an average rate of 3 percent per year since the early 1900s. Copper has been used for the production of many goods, such as power lines, plumbing, cars, computers, as collateral for the Chinese shadow banking sector, as well as many other applications.

But the increase in production has not been smooth during this time. There have been fluctuations around the trend line, including those caused by world events such as World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, the oil shocks in the 70s, and the recessions in early ’80s, ’90s and 2008. Nonetheless, these major events are masked relative to the actual exponential increase as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1: World copper production from 1900-2012.

Data from http://www.minerals.usgs.gov.

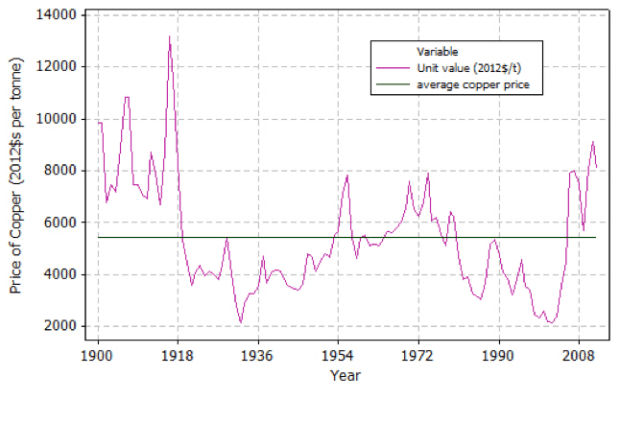

On the other hand, the price of copper (adjusted for inflation) has fluctuated widely around a long term average value of $5,425 U.S. per tonne in constant 2012 dollars (approximately $2.50 per pound) as seen in Figure 2 below.

A price of copper that returns to its average historical price in the long run must imply that the increased (decreased) demand for copper has been met with an expanding (declining) supply of copper. Why does this happen? Market forces are behind this movement.

During an economic upturn, the demand for copper increases, and this increase puts upward pressure on the price of copper. As the price of copper increases, existing firms find it profitable to increase their production, while firms that were “marginal” enter the market, expanding the supply further.

Marginal firms are those at the borderline in terms of economic profits, only entering the market if the price increases. However, the increase in supply causes the price of copper to fall from its initial increase. This natural adjustment brings the price of copper back to what economists call a “long run equilibrium value.”

During an economic downturn, demand for copper drops, putting downward pressure on the price of copper. As the price of copper falls, existing firms will cut production, whereas firms that were at the margin in terms of profitability will shut down their production. These latter actions reduce the supply of copper, causing the price of copper to increase towards its equilibrium value.

Furthermore, technological advances in the extraction of the resource cause an expansion in the supply of copper. This places downward pressure on the price of copper. On the other hand, higher production costs, environmental regulations and other stoppages will put upward pressure on the price of copper.

Copper is a non-renewable finite resource, but the price signal we are getting from the market is that copper has not been scarce over this long period. Figure 2 does not indicate any long run increase in the price of copper.

Even if the price starts increasing in the long run because of the finite amount available, the increase in the price will signal to society to find substitutes which would then put downward pressure on the price. Long run market forces will keep the metal price from rising continuously.

The historical average value seems to be in the $2.50 U.S. per pound range (in 2012 constant $s). The price of copper was $3.16 U.S. per pound on May 15, 2014 (from http://www.infomine.com/investment/metal-prices/copper/). Hence there is still room for the price of copper to fall towards its historical average value. If history is any gauge, it will fall even below $2.50.

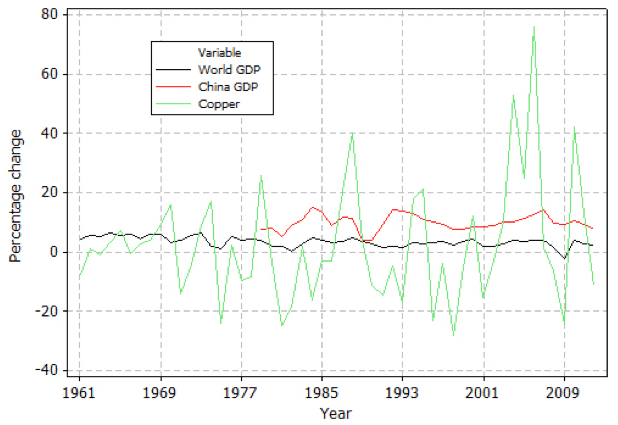

What has puzzled me, though, has been the belief that the increase in the price of copper seen over the last decade (i.e., since 2004) is a result of increased growth in the Chinese economy. This is a false assumption for a number of reasons.

First, China’s growth is not new. China’s very high economic growth started in the late 1970s with the market reforms. Figure 3 plots the GDP world growth rate, China’s growth rate, and the percentage change in the price of copper.

When China was growing very fast in the 1990s, the price of copper was falling, not increasing. The price of copper has been going up and down just like a roller coaster, while the world economy has been growing steadily.

Second, the rising price could be caused by short run supply not increasing at the rate to match the increased world demand for copper. In fact, Figure 1 seems to indicate that production has been below its long run trend since approximately 2004.

Finally, the changes in the price of copper have increased in magnitude recently. Why? Copper trades in a very active financial market and thus responds quickly to any relevant news that becomes suddenly available. The news is incorporated into the price of copper by many buyers and sellers exchanging copper contracts.

For example, news that China is slowing down is instantaneously incorporated into the price of copper even before the slowdown happens. The price of copper will fall immediately, but this will trigger real effects on the production of copper and also on the inputs, including labour, that are used.

Fig. 3: World GDP growth, China’s GDP growth

and percentage change in inflation adjusted

copper price. Data on China’s GDP growth from

http://www.fas.org.

What is my prediction?

I expect the price of copper (adjusted for inflation) to fluctuate closer to its historical average price of $2.5 U.S. per pound (in 2012 constant dollars) over the next 25 years as it has done in the past. Hence, my prediction is that the real price of copper will fall further from its current level towards the historical average price.

China will reach diminishing returns soon as it matures as an economy. This will slow down the world economy. As a result, the price of copper will fall. The reduction in the price of copper will cause mines to reduce the production of copper and “marginal” mines will shut down temporarily. Furthermore, firms that were planning to start new mines will delay their decision to start up. Such changes in production will then cause a reversal in the price of copper.

KGHM Ajax has a very low grade ore and can be considered a “marginal” firm in my view. The value of the firm before taxes is estimated at approximately $108 million using a 12 percent discount rate and a base price of copper at $2.75 U.S. per pound (See Wardrop, 2012). Wardrop’s analysis does not include taxes nor the possible external costs associated with the production. External costs (e.g., health and ecological costs) are not borne by the firm but by the community.

If the price increases sufficiently, the firm if approved will enter the market and extract more copper; if the price falls, it will delay starting operations. If it started production and the price drops, the firm will reduce production or shut down temporarily.

Copper prices change continuously and firms take the necessary production steps to mitigate the impacts but the social-economic, environmental, and ecological risks will be absorbed by the community regardless of the movement of copper prices.

References

Wardrop, Ajax Copper/Gold Project – Kamloops, British Columbia, Feasibility Study Technical Report, 2012. Accessed at:

http://www.amemining.com/i/pdf/2012_01_06_Feasibility_Study_Ajax.pdf

Recycled copper prices and amounts during these times would be interesting ,is copper theft increasing ?

LikeLike

Interesting data about a marginally beneficial and potentially obnoxious project. Are these data to be considered as “facts”? I refer to the supposedly unbiased TV advertising for the project, quoting a local supporter (unbiased, of course), who ludicrously states,”I am in favour of it, and I look forward to all the facts coming out.” Biased? Perish the thought! Only those opposed could be biased!

LikeLike

Excellent analysis, Peter. Easy to understand by those of us who are not economists. Hopefully our citizens and politicians realizes who will be responsible for the potential social, environmental, and health outcomes that might occur if Ajax is approved. Thank you.

LikeLike